Pandolci and Cakes

Patisserie

Pandolci and Cakes

Más información sobre Pandolci and Cakes

From panettone to pandoro, there are many "pani dolci" (sweet breads) that adorn the Christmas tables of Italians, but only one is still called by that name: pandolce genovese.

Legend has it that this typical Christmas cake was invented during a pastry competition held in the 16th century by none other than the Admiral of the Republic of Genoa, Andrea Doria. As with many traditional gastronomic specialities, the origin remains obscure, but what we are fairly certain of is that pandolce was already widespread in the city in the mid-18th century, since we have written evidence of it. It is such a deeply rooted tradition in the city that over time two different versions of pandolce were born: pandolce basso and pandolce alto.

Although the pandolce alto, which is made with mother yeast (or rising yeast), is considered by scholars of gastronomic culture to be the older of the two, the pandolce basso is certainly no less traditional. Indeed, there are those who argue that the pandolce basso may have had a parallel development and descended from some ancient variant cousin of panforti and spiced breads. In any case, in the years when we began to have evidence of the coexistence of these two Christmas cakes, i.e. between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it is believed that the pandolce basso was the pastry cake that could be bought all year round, while the pandolce alto was the home-made cake for special occasions.

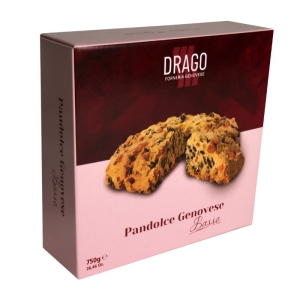

Pandolce basso

Pandolce basso is pandolce made with cake yeast, which makes it resemble a crumbly pastry rather than a bread. In the dough we find candied fruit, sultanas, pine nuts but also egg (an ingredient not present in pandolce alto). It is prepared in less time than the pandolce alto and this must have been one of the reasons for its immediate success. Both pandolces have two leavening times, but only the pandolce basso can be produced in one day.

This is why pandolce basso is also referred to as 'pane dolce svelto' (quick sweet bread) in certain old recipe books, for example in 'La cuciniera genovese' by G.B. Ratto of 1863. In this recipe, Ratto recommended using the following ingredients: 1 kilo of flour, milk, 250 grams of sugar, 10 grams of pine nuts, 200 grams of sultanas, pumpkin, citron, 10 grams of bicarbonate of soda, 15 grams of cream of tartar, 3 eggs and 250 grams of melted butter.

Pandolce alto

The production of a Genoese pandolce alto begins in the morning with the first refreshment of the sourdough starter and ends with the baking in the evening of the next day. Since we have to use natural yeast, therefore with longer leavening times, the preparation of pandolce alto has always required greater attention: today we can better control the temperatures of the production environment whereas before we were more subject to changes in the weather, and even the change from one day to the next from humid to dry weather could compromise all the work. This problem persists when we try to make pandolce alto at home. It is not for nothing that every Genoese family passes down various tricks for the perfect success of pandolce, first and foremost how to keep the dough warm (remember that we are still talking about a cake prepared mainly in December for Christmas...).

The tradition of pandolce genovese

In the enchantment of Italian culinary traditions, the Genoese Pandolce emerges as a symbol of respect, family continuity and well-being. Its presence on the table is more than a treat for the palate; it is a celebration of generations bonding through time.

In ancient times, on its triangular top, the pandolce was adorned with a sprig of laurel, a touch of freshness and prosperity. This gesture, steeped in meaning, took place at the heart of an affectionate tradition: the youngest of the guests would offer the laurel sprig to the head of the family, a sign of respect and gratitude, a tangible demonstration of family unity.

The ceremony continued with the solemn cutting of the pandolce. The first slice was kept for the first guest who came to the door, a kindness that opened the door to hospitality. The second slice, on the other hand, was a precious treasure destined to fight winter illnesses. Eaten on 3 January, St Blaise's Day, this slice was seen as an effective remedy against colds, a protection offered by ancient culinary wisdom.

The distribution of the pandolce began by the head of the family and ran through the generations, an act of sharing that symbolised love and family unity. Each bite is a plunge into memories, a taste of history mixed with the present. Pandolce genovese, more than just a cake, is a timeless bond that unites the past, present and future in a single gastronomic experience. With each slice cut and shared, the tradition lives on, carrying on the legacy of generations intertwined in the magic of pandolce genovese.

Sweet focaccia and other Ligurian Christmas sweets

The 'figassa' was a speciality of Ligurian peasants; it was a kind of seasoned bread about 5 centimetres high and could be either salty or sweet: in the sweet version, butter and sugar were added instead of seasoning it with salt and lard or oil. There was also a Christmas recipe in which sultanas were added, and in wealthier families even candied fruit and pine nuts.

With the strong Ligurian emigration at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, some typical Ligurian recipes crossed the ocean, including pandolce: in South America, one can taste pandulce, evidently a descendant of ours, but which now has little to do with the Genoese one. There is instead a 'genoa cake', a British cake, which resembles a plumcake rich in dried fruit.